Idaho

Red Elephant Mine, Idaho.

I decided to start Western Mining Preservation’s work in Idaho, where my love for frontier mining was born: the Red Elephant mine. It is located roughly six miles west of Hailey. Its development parallels the development of the Wood River Valley. While it was not the largest producing mine in the area, it played a pivotal role in establishing the town of Hailey and the surrounding areas. It played a crucial role in my development as a young man and still plays a role in my development. I went through the process of staking my first mining claim on the lower portion of the site, and the proposed development of the area pushed me to create Western Mining Preservation. This article was created to give you an overview of the mine, the work conducted there, and the site’s general layout now, including any relevant artifacts or areas of interest. It is meant to show our initial work at the site, and document its condition currently.

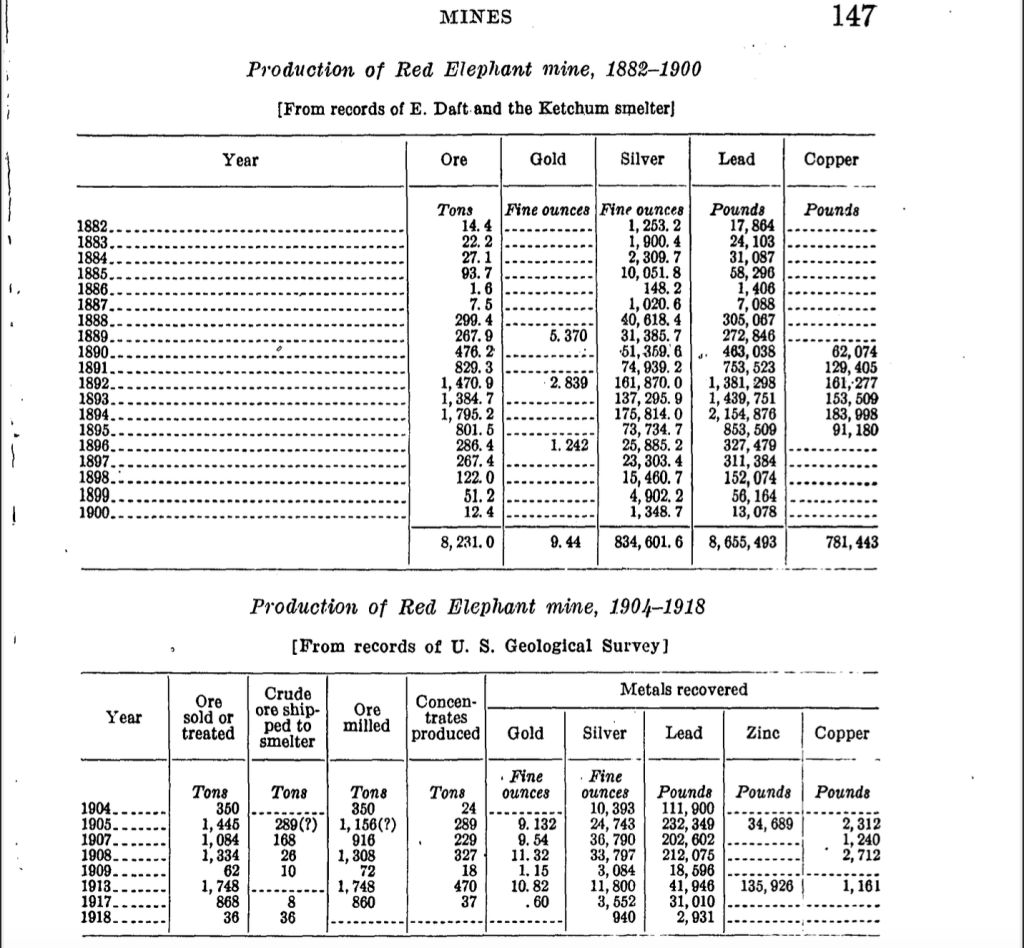

The Red Elephant Mine was one of the early mines of the area, first discovered and worked around the mid-1870s. It is located on the steep south-facing slope of the group of peaks that make up a strong boundary between the area of Croy Creek to the south and Deer Creek to the north and roughly sits one mile west of the important gold mining town/site of Bullion. It was primarily a lead/silver mine, and the overall documented production was in the neighborhood of $1.4 million, including what was made when the tailings were reworked to extract zinc. However, this figure is just an estimate, and I have heard production could have been anywhere between $500,000 and $20 million. Unfortunately, it looks like we will most likely never know the exact number, but we do have some good resources that can allow us to make an educated guess.

The heyday of production for the mine was between the years 1890 and 1898. This was when most of the development work and production was accomplished. The 1930 United States Geological Survey report Geology and Ore Deposits of the Wood River Region, Idaho by Joseph Umpleby, Lewis G. Westgate, and Clyde P. Ross provides one of the most in-depth descriptions of the mine I have found. Joseph Umplebey visited the area in 1912 and 1913 and compiled much information on the Red Elephant mine. He resigned from the USGS in 1919 before the full report was published, and the other authors had to help finish his piece. Clyde Ross visited the area in the early part of the 1920s and updated Umplebey’s notes to reflect the current workings and situation of the mine. He continued visiting throughout the 1920s, and all the information I have included on the history of the mine is from this report.

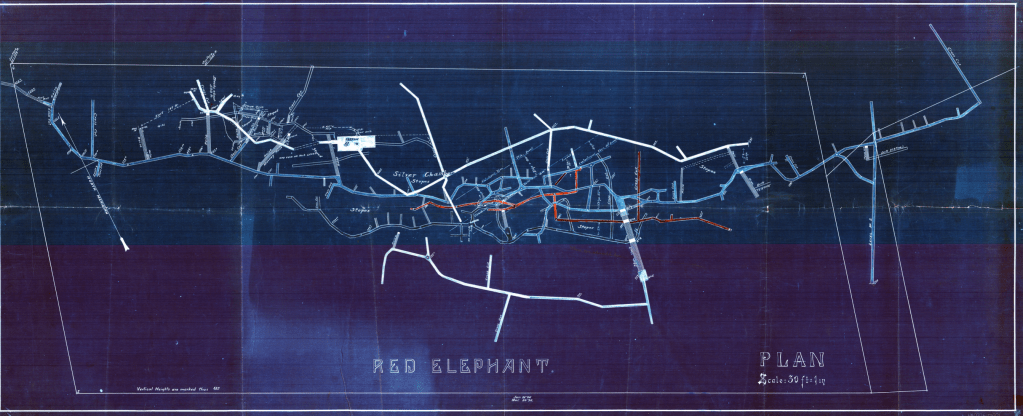

At the time of publication, 1930, the development of the Red Elephant mine consisted of approximately 9,000 feet of workings on six levels. The main working level was level two; most ore came from on or above level two, and none was found below level five. The ore was distributed in a shape generally representing a blunt wedge pointed downwards. They were able to access three of the stopes on the level when they visited, and this allowed them to make some general observations of the condition of the mine, the general geology of the area, and the scope of the ore bodies.

According to the report, there appeared to be five distinct ore bodies that had been worked out on level two, and a few high-paying ore shoots yielded a decent amount of ore. One of which, the Hard Rock shoot, netted the mine owners around $80,000 until it terminated against a fault. Around ninety feet north of the Hard Rock shoot was the Coeur d’Alene shoot, guessed to be the same ore body as the Hard Rock shoot. It was shifted in position by transverse displacement of the rock, and the miners found it after searching for the continuation of the Hard Rock shoot. The Coeur d’Alene continued for about 100 feet and then was faulted again, throwing the vein about 30 feet east, turning it into the Silver Chamber shoot. This was around 12 feet wide, showed solid galena (lead/silver ore), and continued to nearly the 500-foot level of the mine.

One last shoot, the Flynn shoot, was its own separate shoot. It contained the highest quality ore in the mine; individual miners described it as being almost fifty feet thick at specific points with large galena deposits throughout. The miners had long since exhausted the ore in the Flynn at the time of the visits in 1913 and the 1920s, and none of the workings were accessible, so I do not have an accurate description of their makeup or composition.

At the time of the visit in 1913, the Red Elephant Consolidated tunnel was being driven into the mountain to explore the hanging-wall country rock for possible off-shoots of the ore bodies. Its portal is located at 6,235 feet and can still be seen today (although it is long since caved and overgrown with vegetation). In 1913 it was 1,280 feet long; in 1919, the tunnel was 2,000 feet long and had cut a vein carrying ore. They had done some work on the vein; however, no work had been done on the tunnel at the time of the visit. There were a few attempts to restart operations at the mine in the mid-to-late 1920s, but all work appears to have been suspended near the end of the 1920s.

This is where most of the information on the mine ends. But this is not the end of operations at the mine. From here on, barring any undiscovered source of records (which I am currently looking for), I am guessing at the history of the mine, using some of the archaeological evidence to guide me.

After World War II, mining saw a slight revival in the Wood River Valley region. Records are surprisingly hard to come by, but it seems that many of the major mines in the area were either worked by those who wanted to reprocess their tailings or by those who thought it was worth exploring the old workings for ore bodies the miners of the past missed. The same appears to have happened with the Red Elephant mine.

When I look through the history of those who possessed the mining claims that make up the Red Elephant group in the past, companies like Exxon Mobile and Ford Motor came up. However, I cannot find any information on the extent of their work at the mine, if any. The more recent holders of the claims did little, if any, work on them.

Most of the workings are long since caved, and nearly all of the equipment from the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries is long gone. I have found a few horseshoes from, as far as I can tell through my research, the late 1800s or early 1900s, but not much else from that time. I found a part of a heavily corroded chain and hook and some nails, most likely used as part of a hoist system. They are all in poor condition and were not in their original locations, having been piled up in a fire pit on the site and exposed to fire many times.

I have found more artifacts from the mid-20th century recently. Down the road from the Red Elephant is another mine whose name I have yet to be able to identify conclusively. It is off the road, hidden in willows and under the boughs of spruce and aspen trees. This site was most definitely worked during the mid-20th century, as there are concrete footings for pumps and compressors, oil cans, and the remains of rubber-soled boots strewn through the area. I have followed the road from this site to the Red Elephant and found many other mid-20th-century artifacts, such as nails.

As I explore the Red Elephant area, I find the same remains. Parts of rubber soled-boots, nails that are distinctly mid-20th century in design and manufacture (they have round heads), and the remains of motor vehicles and other odds and ends. I have found fireplace mesh, the foot of a bathtub, and various drums that contained unknown substances such as oil or coolant. These artifacts are in poor condition, and it is difficult to identify the year of manufacture, what they held, and where they may have come from.

What is interesting is the lack of relics from the 19th century. The typical practice is to remove all the monetarily valuable equipment from a mine once it ceases operation. As people reworked these sites in the 1950s and 60s, they likely either removed or buried whatever remains existed. I firmly believe that further archaeological work, especially digging in certain areas, will uncover more artifacts from the 19th century. I know this because I explored the workings further up the gulch.

From the lowest level of the mine, what I believe is The Red Elephant Consolidated shaft, is around a one-thousand-foot hike up the mountain to the upper workings, the main Red Elephant shaft, and its associated tunnels and adits. There are two ways to climb: the long way, retracing one’s steps back about a half-mile to the y-intersection where the road splits, or going up the gulch along the remains of the road that connected the mines at one time. The road up the mountain at the y-intersection is the more leisurely walk because it is in decent condition, even if it is a steep climb. It affords a better view of the entire workings and doesn’t require a person to bushwack.

The shorter route leads up from the Red Elephant Consolidated shaft along what once was a road. It is not a road now, and there are no easily distinguishable paths to follow when going this way other than to keep climbing up. A small creek flows intermittently down this gully, but following it can be difficult with the deadfall and other obstacles that have accumulated over the years. Side-hilling is the best bet, and making your way out of the aspens and willows and onto the bare hillside is easier than stumbling through the woods.

It is a three hundred or so foot climb to the Caledonia Shaft (again, this is a guess on the name, as I am still looking for maps that allow me to identify the various shafts with 100% certainty). It is easy to locate this area due to the size of the waste piles that sit in the middle of the gully. It is around 300 or so feet below the primary Red Elephant mine, and I have estimated the height of the waste pile at about thirty-five feet at its highest point. The sides of the wastepile are bare, while the top, which the miners leveled out, is covered in thick sagebrush, grasses, and willows where a spring flows over it.

This waste pile contains the remains of narrow gauge ore cart tracks, pipes, and other artifacts sticking out of the side. My research shows these tracks resemble those made in the late 1800s or the early 20th century. They are heavily corroded in some places, but others are remarkably well preserved. I have yet to do any excavation work, although it looks like there are a few artifacts that were buried when the mine ceased operations. I plan to excavate this waste pile if I can get permission. It could contain some interesting artifacts from the end of the 19th century.

More workings are about 200 feet in elevation gain up the hill from here. One is a tunnel cut into the hillside directly off the northeast side of the road that winds its way up from the bottom of the canyon. There is also an old tunnel and a waste dump to the northwest; however, it is so overgrown with sagebrush that it is nearly impossible to see. The climb is through a small gully, and it is steep and rugged for about two hundred feet before it leads you to the road. There are some scattered pieces of debris in the gully; they seem to be mostly rusted sheet metal and the remains of old cans. They look to be from the middle of the 20th century.

When you reach the road, you are greeted by the looming waste pile from the primary Red Elephant mine to the northeast and the imposing wooden ore bin directly to the north. This is where the Red Elephant starts to capture the imagination. Looking at waste piles is one thing; seeing the ore bin is another. It shows the scale of the operation here on a smaller scale than would have been possible to see a hundred years ago; it shows the human element in the expanse of rocks. Another thing you will see on approaching this area is the dumps higher up on the hillside. The workings of the mine extend up to nearly 7,400 feet before they stop.

The ore bin looks to be from the mid-20th century. I have yet to confirm this through historical records; however, the nails and fasteners used to hold it together appear to be from this time. It is roughly twenty feet tall at its highest point and has three chutes facing the road where trucks or carts would have been backed up and the ore loaded in.

The ore bin is deteriorating, and I have noticed the wood starting to slump inwards about halfway up the front face over the last year. When I compare the photos I took a year ago to my trip just a few days ago, I can see the difference. There are no noticeable differences in the wood debris scattered around the bin’s base; I did not see any new material there that may have fallen off over the winter. I did notice that the internal structural support sustained some damage throughout the winter, and this will likely continue unless specific steps are taken to shore up the internal structure of the bin.

To the west and a little south of the ore bin is an unidentified metal object that looks like a boiler or furnace. It is sitting on its side, about fifteen yards from the ore bin, in a depression on the side of a bank. There are no markings on it, and I have yet to be able to identify its exact use. Interestingly, when the Idaho Geological Survey conducted operations in Bullion Gulch around the Jay Gould Mine, one gulch away to the east of Red Elephant, they found similar objects. They labeled them as mystery objects, possibly boilers. They served some purpose for the miners, and their use would be self-evident to anyone working in the mines. I am still determining from what time this particular object originated. While it seems likely that they are from the mid-20th century, it is entirely possible that they originated in an earlier time. I will continue to research and see what I can learn about it.

Around the ore bin is the waste dump from the Red Elephant mine. If you look through the rock piles, you can find a good representation of the rocks encountered inside the mine and some genuinely great samples of pyrite and galena. There are plenty of pieces of ore left over to look through to get a good grasp on the geology of the mine. Most are oxidized, stained red and brown from the minerals.

On the top of the waste pile is a decent amount of ore cart tracks and piping sitting half-buried in the debris. As to what era they are from, I do not know, but they are slightly slimmer in design than the ones I found down below at the Caledonia Shaft. The pieces sticking out of the ground are only small parts of a much more extensive network of tracks, most likely buried in the waste piles themselves. You can visually estimate the path the tracks followed from the mine portal, about fifteen yards away to the east, and to the ore bin, about twenty-five yards out to the southwest. There either was a platform for the tracks to sit on so the miners could move the ore carts from the mine and dump their contents into the ore bin, or the tracks were laid across the ground to help them do the same. Any remnants of that platform are long gone, as are any clues to the direction the tracks took, but one can guess by looking from the portal to the bin. The loading area of the bin sits roughly ten feet lower than the portal, so gravity may have been a tool the miners used to help them move the heavy carts. The pictures I took of this area did not turn out clearly. I will return and re-take them and then update the post. However, I did get some good videos of the site, which I will include in my overview of the area at the end of the post.

The portal of the Red Elephant Mine itself is long since caved and sealed up. There are scattered pieces of timber around the waste dumps and a few large pieces of ore by the portal itself, but I could see no evidence of cart tracks or any other artifacts on all of my inspections of the area. The ground here is wet, and there must be a runoff of water coming from the portal; although it is so slight, I could not find any free-flowing water. In all, it looks remarkably plain for the main shaft of an important mine. Only the size of the waste piles gives any indication of the extent of work that was done inside.

From here, there are two ways to start working up towards the workings above this tunnel. One is to retrace your steps and head down to the road by the ore bin. If you follow this, it will snake you around and up the mountain to the next area—a journey of probably a third of a mile.

Another way is to head straight up through the little gully on the left of the Red Elephant shaft. I have taken both ways up, and neither is better. The direct route through the ravine and climbing up the waste piles from the shaft about forty feet above the Red Elephant shaft will save you time, but it is a more challenging climb. This is how I usually go when I ascend the workings, and what it loses in ease, it makes up for in less distance traveled. There are no artifacts to be found here, only the remnants of the waste piles that have eroded into the gully through the years. It is a short but challenging climb, and the rock is often loose and can give out if you ignore your footing.

The next level is a waste dump from a horizontal and vertical shaft in the mountain to the northwest. The horizontal shaft is cut into the mountainside right off the roadway, caved, and filled with stone. To the right (north) of this is a vertical shaft off the road about thirty feet. The vertical shaft was cut directly into the main ledge of material and went down for about ten feet before it was filled in with dirt and rocks. I am not entirely sure what this shaft was called, and my diagrams of the workings have done nothing to illuminate this mystery. It appears to have been a well-used shaft. There are no artifacts in plain view around the shaft, although I can’t help but wonder what I would find if I started to dig around it.

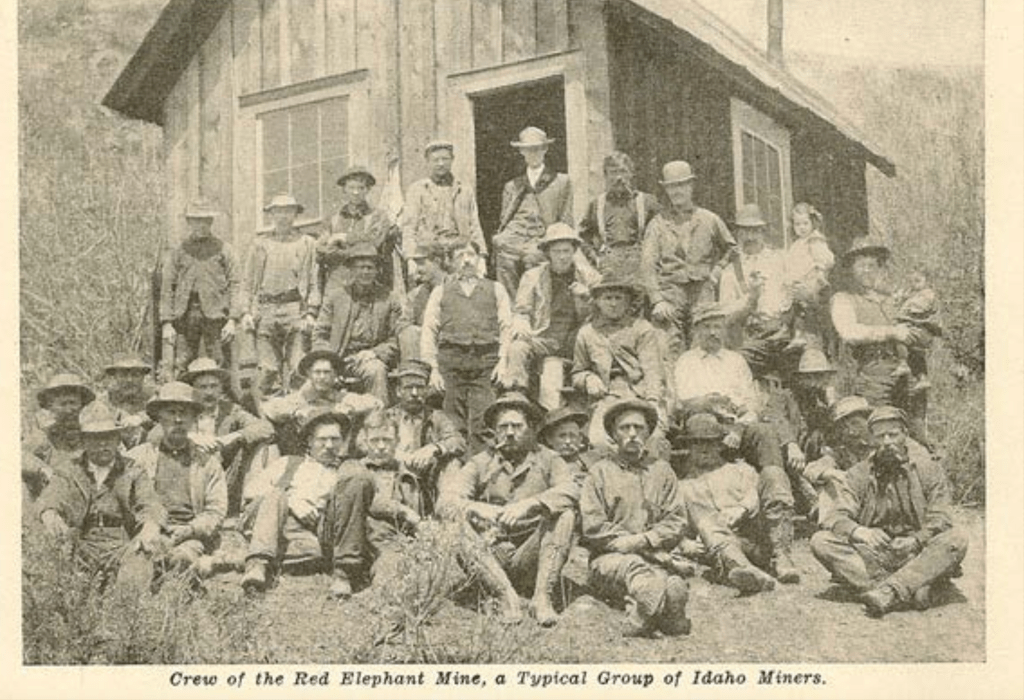

To get to the highest working levels of the mine, you take the road southeast up the hill from this shaft and climb up to the saddle that separates Red Elephant Gulch from Bullion Gulch to the east. The climb here gets steeper, and every time I start this journey past the 7,000 feet in elevation mark, I can’t help but feel a great respect for the men who worked these mines. It is open on this south-facing slope. It is nearly always windy and dry, and living and working here would have taken a special breed of person.

After about three hundred or so yards, the road winds up to the saddle, and you can see where it branches off and goes down the other side of the mountain and into the trees that cover the north-facing slopes of the Bullion Gulch area. Down this road lies the Jay Gould Mine and a few other unidentified ones. I will explore this area in the future and will not go into any more of the history right now.

At the saddle, a small piece of rebar is standing vertically out of the ground, and a large pipe is lying on its side in a northeast-southwest-facing direction right alongside it. The small piece of rebar is stuck into a bit of concrete. Written into the concrete when it was still wet is “Saddle: 6/26/67.” I am unsure if this was a mining claim boundary, although I have seen similar markings used here to denote mining claim boundaries. Regardless, it is a remarkable piece of history. I wonder who poured the concrete and wrote that inscription.

The road bends to the northwest from here and leads to the highest levels of the workings. On the right, there are a few dumps and waste piles. I do not know the names of the mines, and I only visited some of them as they are outside this piece’s scope. When I work on the Jay Gould Mine, I will make the ascent and document them. The road rises a decent amount, and it undulates its way up the ridgeline and then crosscuts the side of the mountain up to the last workings. This spot is nothing more than an indentation in the ground and a slight depression on the side of the mountain. I wonder if this was a shaft or something else. There is no archaeological evidence this high up, at around 7,200 feet, and I can’t find any references for what was done on this level in my research. Perhaps a detailed excavation would allow some clarity.

From here, it is possible to see almost the entire scope of the Red Elephant’s workings as you look down the mountain. It is incredible that people could do so much in such a hostile place, on the side of a mountain, without much support.

I hope this gives you an understanding of the basic workings of the Red Elephant Mine and why it is such a special place. I will include all the references I can find for it and historical and current photos of the workings. If you decide to visit, please remember that these historically important areas belong to the State of Idaho. Do not remove any artifacts or damage any of the structures. Please immediately report any vandalism or removal of artifacts to the Blaine County Sheriff’s Office. I can tell you from experience that they take these reports seriously and quickly respond.

Please check out this link to the Idaho Geological Survey’s site on the Red Elephant Mine. It contains many historical documents and pictures from the mine’s past and provided me with much of the information I used to create this article.

Thank you so much for reading. Please reach out if you have any questions or want to learn more.

Leave a reply to Idaho Cancel reply